Reading done on October 16 2018

"Defining Visual Rhetorics - Introduction"

- by Marguerite Helmers and Charles A. Hill - 2004

- Edited by Charles A. Hill and Marguerite Helmers

Through out this book, the essays of Charles A. Hill and Marguerite Helmers (2004) are focused on the question: "How do images act rhetorically upon viewers?" (1).

"Images surround us in the home, at work, on the subway, in restau- rants, and along the highway. Historically, images have played an important role in developing consciousness and the relationship of the self to its sur- roundings. We learn who we are as private individuals and public citizens by seeing ourselves reflected in images, and we learn who we can become by transporting ourselves into images" (Hill and Helmer 2004, 1).

“One of the crucial media- tions that occurs in the history of cultural forms is the interaction between verbal and pictorial modes of representation [...]” (W. J. T. Mitchell. as cited in Hill and Helmer 2004, 1).

"As Wibben indicates, significant facts about images and their interpretation and important questions about the relations of all images to human mediation emerged from the September 11 attacks. Strong national symbols such as the eagle and the flag are liberally in use in the popular and mass media as a means of gathering together the imagined national community, and to these patriotic and sentimental images the twin towers of the World Trade Center have been added in the way that the red poppy came to symbolize the First World War. Together, these symbols form an expressive syntax for what Barber calls American “monoculture,” a “template,” a “style” that exemplifies a certain lifestyle—but in turn begins to demand “certain products” (82). Symbols resist individualistic interpretation because they are overdetermined by customary usage, embedded so frequently in conventional discourse that they rarely take on a reflective, individual meaning. As Edwards, Strachan and Kendall point out in their contributions to this book, national symbols are employed as a visual shorthand to represent shared ideals and to launch an immediate appeal to the au- dience’s sense of a national community" (Hill and Helmer 2004, 4).

"One of the ways that we understand this[an image discussed in a previous page] photograph is through its reference to other images. Thus, one of the ways that images may communicate to us is through intertextuality, the recognition and referencing of images from one scene to another. The reader is active in this process of constructing a reference. If the reader is unaware of the precursors, the image will have a different meaning, or no meaning at all" (Hill and Helmer 2004, 5).

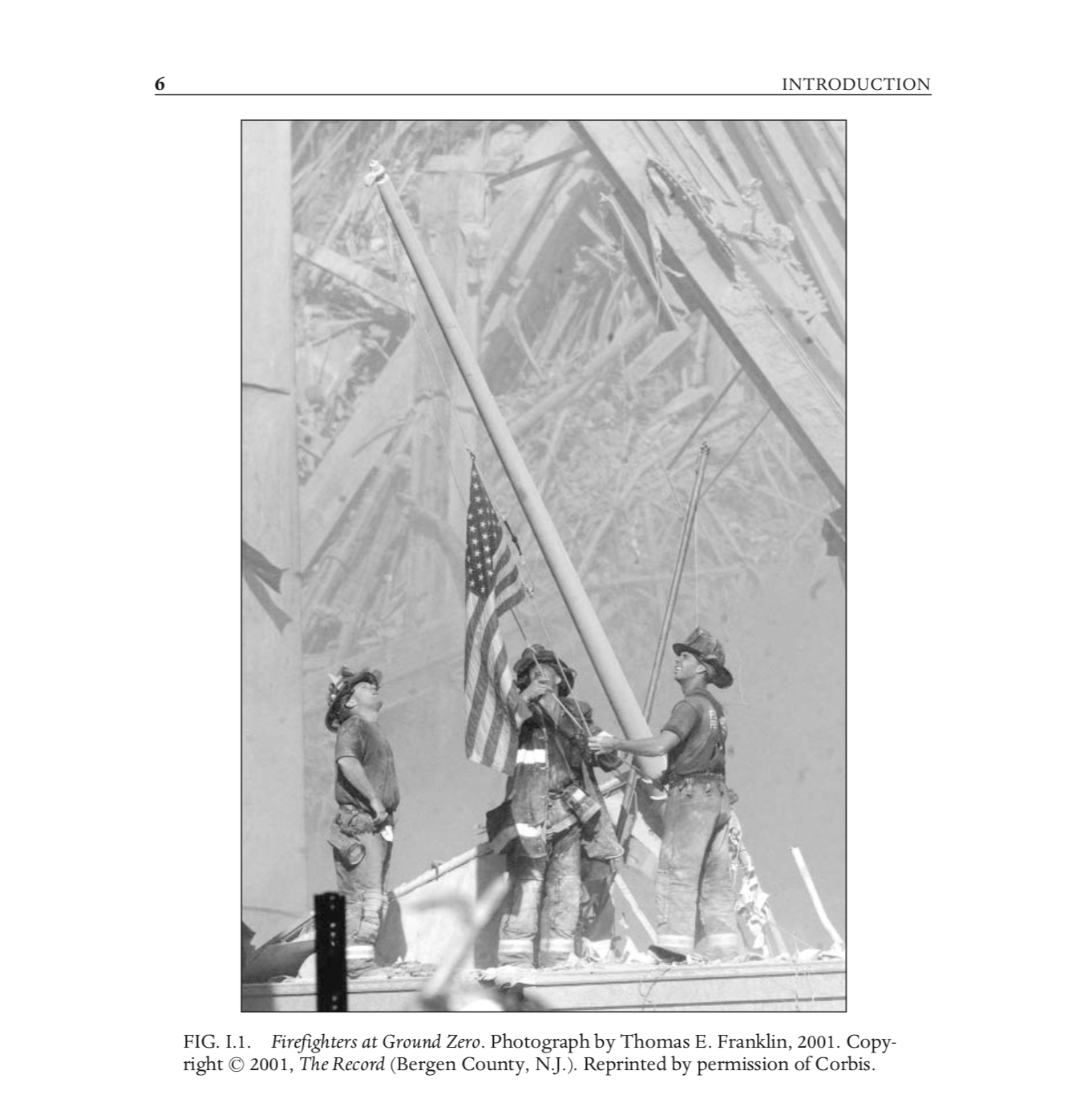

"The simple composition of the image [FIG. I.1.-above] is both essential and non-essential to the meaning. The fact that there are three figures involved in the flag raising, rather than two or five, invokes the Christian Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. Inscribing the Trinity over the rubble of the Trade Center offers a corrective to the “Islamic fundamentalism” of the ad hoc pilots of the aircraft that blasted into the buildings in the morning. The immediate symbolic value of the American flag encodes “appropriate” and conditioned responses of patriotism, loyalty, and invincibility" (Hill and Helmer 2004, 7).

The authors claim that "[i]n Franklin’s image, the flag’s importance is emphasized because it occupies the central axis of the photograph. The diagonal placement of the flagpole across the ground of the rubble physically cuts across the devastation with something whole, purposeful, strong, and integrated. It marks the connection to an imagined community called “America” that, in turn, recognizes the photograph as symbolic" (Hill and Helmer 2004, 8).

Accordinly, Hill and Helmer claim that "New York firefighters were the first on the scene and were inside the towers when they collapsed, leaving 343 firefighters dead. The rubble—the back- ground to this photograph—provides meaning to the image, for it is this “ground” of rubble, which encompasses half of the scene but does not intrude on the activities of the men, that gives meaning to the figures’ resilient action. They are not rescuing or digging out here, but taking time to reflect on the spirit that gives meaning and purpose to the activities at Ground Zero. It is because the men stand in the foreground that the photograph achieves its power. Imagine a different photograph, one taken through the rubble, framing the men, dwarfed by the gothic arcs of the burning, decaying steel, or, as seen through the charred cruciform windows of buildings adjoining Ground Zero. Decreasing the physical relationship between men and rubble would decrease the importance of the working man, the New Yorker, in overcoming disaster. It would place disaster in the foreground and as the protagonist of the photograph. In fact, photographers such as James Nachtway, Anthony Suau, Susan Meiselas, and Gilles Peress made images such as these; yet these images failed to become icons" (Hill and Helmer 2004, 8).

the authors' attentiveness provices clues and they claim that "[a]t a simple denotational level, however, there are questions about Franklin’s Ground Zero Spirit that cannot be answered without association to Rosenthal’s photograph from Iwo Jima. For example, abstracting ourselves from immediate history, how do we know, on the basis of the photograph alone, that the three firefighters are raising the flag? Is it not possible that they are lowering a flag left standing amidst the ruins of the Trade Center? Secondly, without the context of the photograph and the immediate, collective memory of the events of September 11, there are no indications that the photograph takes place in New York City, amidst the rubble of the former World Trade Center, or in September 2001. The necessary historical detail that contextualizes the photograph also gives the photograph its profound meaning. Furthermore, the Ground Zero Spirit photograph is significant because it is like and unlike Iwo Jima" (Hill and Helmer 2004, 9).

Furthermore, they assert that iam’s "[i]conographically, to look downward is to lower, and lower the spirits of the spectator. Looking up, as in the Renaissance images of the Madonna and the saints, represents hope" (Hill and Helmer 2004, 10).

"As with any work of art (or photojournalism) in the age of mechanical reproduction, the question of what the photograph means depends on its dissemination and reception" (Hill and Helmer 2004, 11).

The authors refer to Charles Sanders Peirce's theory of signs and representation that was derived from John Locke's essay Concerning Human Understanding, in which Locke proposed the study of what we know today as "semiotics" (Hill and Helmer 2004, 15) through which Peirce distinguishesthe triadic theory of icon, index, and symbol. This theory is frequently used byrhetoricians to discuss both language and images as these three establish a formal terminology for considering different types of imagistic sign systems, from representational, through diagrammatical, to allegorical (Hill and Helmer 2004, 15).

"Two levels of terminology establish the relationship of sign to referent. At the first level, Peirce contended that a sign stands in for an Object; it “tells about” its Object (100). He gave this sign the name representamen. The represen- tamen is rhetorical; it “addresses somebody, that is, creates in the mind of that person an equivalent sign” and this equivalent sign is called the “interpretant” (Peirce 99). The interpretant represents an idea that Peirce called “the ground of the representation” (qtd. in De Lauretis, Alice 19). The interpretant is thus a mental representation; it is not a person. Thus, both representamen and interp- retant relate to the same Object. In using the work of Peirce to establish a semiology of art, Mieke Bal and Norman Bryson contend that the interpre- tant is associative and connotative. “The interpretant is constantly shifting; no viewer will stop at the first association” (189). Nonetheless, this does not mean that interpretants are unique; interpretants are shot through with “culturally shared codes” (De Lauretis 167). “Interpretants are new meanings resulting from the signs on the basis of one’s habit. And habits, precisely, are formed in social life” (Bal and Bryson 202)" (Hill and Helmer 2004, 15).

The authors claim that "[o]nce these terms are understood, they facilitate understanding Peirce’s dis- tinction between icon, index, and symbol. This trio of signs is not graded or hi- erarchical; rather, each term describes ways that different types of images may be understood. The icon may be abstract or representational; it possesses a character that makes it significant (Hill and Helmer 2004, 15).

"Peirce refers to the icon as an image" (Hill and Helmer 2004, 15).

"The index [...] depends on the existence of the Object to have left what Jacques Derrida, in Dissemination, would later call a “trace.” Therefore, the indexical image holds an existential relationship to its Object and often raises in the viewer a memory of a similar Object. The classical example of an indexical sign is a bullet hole. The interpretant indicates, “here is a hole in the front door” and relates the hole to other holes, but not to the Object (a bullet making the hole) because the Object—the bullet and the gun—are missing. In Roland Barthes’ words, the index “points but does not tell” (62). Peirce describes the index as a diagram" (Hill and Helmer 2004, 16).

"The symbol is the most abstract of the three sign types. It depends on the interpretant, that is, the mental representation in the mind’s eye" (Hill and Helmer 2004, 16).

The authors claim that "the creator [of the image] assembles and arranges “blocks of meaning” so that the description becomes yet another meaning" (Hill and Helmer 2004, 17). Having said this, they look into Barthes’ insights for the study of visual rhetoric who claims that "the assembling of these “blocks of meaning” is a rhetorical act" (Barthes as referred to in Hill and Helmer 2004, 17).

"“Visual representation gives way to visual rhetoric through subjectivity, voice, and contingency,” comments Barbie Zelizer. With photojournalism, or with other representational media, we are able to project “altered ends” for the representations we see. This insertion of the spectator’s desires for the future is like the tense in verbal discourse, as tense can locate a moment into the past (that which has already happened and cannot be changed; visual representation), the present (what Zelizer terms the “as is”), or the future (the moment of possibility that Zelizer calls the “as if ”). Rhetorically, “as if ” has the greatest power because it directly involves the spectator and depends on the spectator’s ability to forecast and manipulate contingencies in order to create a meaning (Hill and Helmer 2004, 17-18).