Reading done on November 30 2017

"Documenting the Virtual ‘Caliphate’: Understanding Islamic State’s Propaganda Strategy"

- by Charlie Winter (Quilliam’s Senior Researcher on Transnational Jihadism) - October 2015

- Foreword by Haras Rafiq

- ISBN number – 978-1-906603-11-4

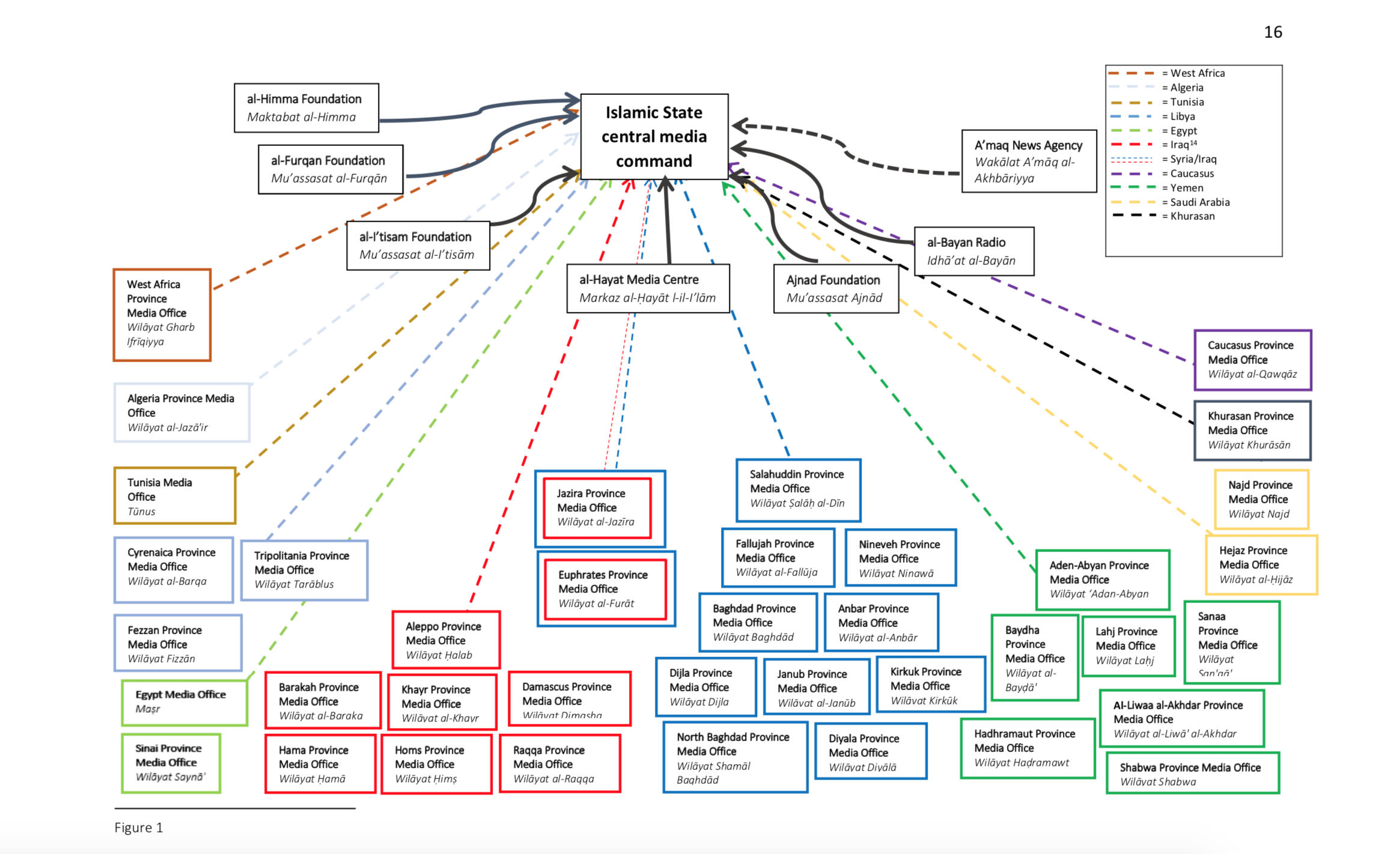

- photo source: The Islamic State media Organization, from Documenting the Virtual ‘Caliphate’: Understanding Islamic State’s Propaganda Strategy, page 16.

In his foreword, for this report, Haras Rafiq, Managing Director of Quilliam, claims that IS has a carefully cultivated and choreographed imagery (Winter 2015, 4).

In 2015, Senior Researcher Charlie Winter in Quilliam Foundation, a London-based think tank that focuses on counter-extremism, specifically against Islamism, conducted a research deconstructing the Islamic State’s media organization, its strategy and its outputs (Winter 2015, 6) in order to understand how the group projects itself (Winter 2015, 8) in order to understand the strategic thinking of the group’s brand and messaging (Winter 2015, 8). Between 17 July and 15 August 2015 (30 days), the Islamic month of Shawwal [1], Winter (2015) compiled 1146 media outputs from the Islamic State and recorded these outputs “according to their primary narrative and, if applicable, sub-narratives” (5).

Through this research Winter concludes that while the Islamic State has a broad consistency in its narrative, it nevertheless shifts on a daily basis depending on the group’s priorities (Winter 2015, 6). The shift in narrative stays within the pool of the primary narratives of the IS media outputs, which consist of: mercy, belonging, brutality, victimhood, war and utopia (Winter 2015, 6). Winter (2015) claims that on one hand, more than half of the IS media output focused “on depicting civilian life in Islamic State-held territories” focusing on the ‘caliphate’ utopia (6). The IS aimed to attract supporters by appealing to them through the demonstration of economic activity, social events, abundant wildlife, unswerving law and order, pro-activity, and flawless warmth and sincerity (Winter 2015, 6). Winter (2015) claims that “in this way, the group attracts supporters based on ideological and political appeal” (6). On the other hand, the Islamic State portrays their military in stasis or during offensives with few occasions of its defensive war depiction (Winter 2015, 6). This shows their need to preserve the aura of supremacy and momentum (Winter 2015, 6). Furthermore, according to Winter (2015), a large proportion of IS’s military-themed events depicts fighters “with mortars and rockets being fired towards an unseen enemy (6). Most interestingly, he claims that “given the locations from which many of these reports emerge, as well as the fact that the aftermath of such strikes is rarely, if ever documented, it is conceivable that these low-risk attacks are falsely choreographed to perpetuate a sense of Islamic State’s constantly being ‘on the offensive’” (Winter 2015, 6).

Methodology

a) Locating the source

The primary sources used nowadays by jihadist groups are social media such as Twitter, Tumblr, Facebook, and peer-to-peer Apps such as Kik, Surespot, Telegram (Winter 2015, 10).

b) The dissemination structure

Since the summer of 2014, due to necessity, rather than choice, the Islamic State stopped using ‘official’ accounts on Twitter as they are easy targets for suspension before gathering followers or disseminating media (Winter 2015, 11). Having said this, Winter (2015) claims that the Islamic State had to adapt and adopt new methodology - hashtags, as Twitter does not suspend nor blocks them (11). He states that by “ using an organically defined set of tags, Islamic State’s official disseminators can simultaneously be effective and low-key. They do not require official branding or a large following to have a large impact. Indeed, the more they blend in with the crowd, the better” (Winter 2015, 11). Moreover, Winter (2015) claims that as there are multiple ‘official’ initial disseminators, if some are removed, others will always be present (12). Winter (2015) claims that the only way to compile a full dataset of all Islamic State’s media output “is to systematically monitor each of the organization’s designated hashtags (12). He gives 2 reasons for this: First, he explains that as there is no single account responsible for Islamic State’s official media output on the Internet, identifying and monitoring initial disseminator accounts is not enough to get hold of all outputs (Winter 2015, 12). Second, the Twitter accounts that act as an archive for the IS outputs are insufficient sources due to their periodic absences, suspensions, or lapses of interest (Winter 2015, 12). Therefore, he states that his research tracked hashtags, not users (Winter 2015, 12). These media outputs consisted of photographic reports, audio statements, magazines, online articles and videos (Winter 2015, 14). Winter recorded all media outputs according to 7 variables: date, country, location (if applicable), production unit, medium, language and title (Winter 2015, 14). While Islamic State regularly releases foreign language media, all the data for this research was compiled using Arabic-language sources; Winter claims that the IS’s the majority of the foreign-language supporters are restricted by their language skills, and therefore they would have offered a “partial view of the full picture” (Winter 2015, 14).

c) Building the archive

Charlie (2015) claims that "the only way to compile a full dataset of all Islamic State propaganda is to systematically monitor each of the organisation’s designated hashtags"(12).

d) Refining the archive

Over the 30 day data collection period, a total of 1146 media outputs were recorded in their original Arabic form. Prior to the analysis, the title and content of each of the media output was translated along with the respective production unit, language and location, then they were sorted by their primary narrative – brutality, mercy, belonging, victimhood, war and utopia, of which the latter two are further divided (Winter 2015, 14). Winter (2015) explains that the narratives war and utopia are further divided into sub-categories (14). According to Winter (2015), the war narrative consists of 14 subcategories: preparation, offensive, defence, attrition, martyrdom panegyrics and summary; and for utopia: economic activity, expansion, governance, justice, religion, social life and, lastly, nature and landscape (Winter 2015, 14).

Thematic Analysis

Mercy narrative depicts the idea that Islamic State is willing and able to grant clemency to those who repent: at these carefully orchestrated events, people – fighters and civilians – would be shown pledging allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi en masse (Winter 2015, 18).

Belonging narrative stresses on the collective nature of the Caliphate (Winter 2015, 19).

For example: photos and videos showing fighters relaxing with each other, drinking tea and enjoying themselves, still convey a particularly appealing story of the collective (Winter 2015, 19).

Brutality narrative, according to Winter (2015) has the intention to intimidate enemies, provoke irrational reactions from the media and separate communities (21).

Victimhood narrative portrays the idea that Sunni Muslims are persecuted by a global conspiracy. This narrative acts as a justifier for the IS existence and for its brutal acts (Winter 2015, 23).

I would furthermore link this narrative of victimhood to Utopia, and the Islamic State acting as a saviour for the Sunni Muslims and giving them the opportunity to live in the Caliphate away from the “global conspiracy”.

War narrative While the Islamic State is fighting on both defensive and offensive fronts, it is the latter that give the most attention to and depict it to their audiences (Winter 2015, 24). “In places where the fiercest fighting is taking place, there tends to be a marked absence of the production of war events” (Winter 2015, 25). According to Winter (2015), this is due to the fact that the Islamic State needs to sustain support and conserve the perception of the apocalyptic force (Winter 2015, 24).

The war narrative is further divided into 7 subcategories:

a) Summary: retrospective reports on the previous day’s military accomplishments (Winter 2015, 26).

b) Preparation: (for example: military in stasis) They are intended to impress upon current and prospective members of Islamic State the professionalism, stoicism and well-equipped nature of its standing army (Winter 2015, 26).

c) Defence: According to Winter (2015), “the Islamic State cannot afford to be perceived as ‘on the defensive’, because its chief appeal is the perception of its political and military supremacy” (Winter 2015, 26).

d) Attrition: According to Winter (2015) in this war narrative subcategory, the images are limited to that of “mortars, Qa’qā’ and Katyusha rockets being fired at the unseen enemy” (27) without providing any evidence that an enemy is on the receiving end (27). Winter (2015) claims that this makes sense, given the Islamic State’s “history of duplicity” (27). In footnote, he gives an example of this claim, of August 2015, when the Islamic State “released ‘Fallujah, the graveyard of the invaders’, a video in which was depicted what is, at first glance, a recent attack on forces loyal to Baghdad. In reality, as noticed by Daniele Rainieri, the raid had actually taken place the year before no later than October 2014, when a photo report was released on it. See @DanieleRainieri, Twitter, 21 August” (Winter 2015, 27).

e) Offensive: This subcategory narrates attacks or raids while “showing off the efficiency and supremacy of the Islamic State’s fighters" through the depiction of its soldiers “as courageous and committed” (Winter 2015, 27), which according to Winter (2015) has the intention of shaming sympathetic observers into volunteering (25).

f) Aftermath: In this subcategory of war, the Islamic State fighters are depicted celebrating over war loot (anything taken fro someone else during war), defiling the bodies of the opponents, parading prisoners, examining destroyed tanks (Winter 2015, 27), and showing trenches filled with corpses (Winter 2015, 28). Winter claims that these depictions all mean a declaration of hegemony (Winter 2015, 29).

g) Martyrdom panegyrics: In this narrative subcategory eulogizes (praises enthusiastically) the Islamic State martyrs and celebrates those killed for its cause (Winter 2015, 29). While providing examples as a footnote [2], Winter (2015) claims that the Islamic State furthermore creates a celebrity culture around its martyrs and circulates officially IS branded photographs and sometimes videos of IS martyrs/heroes with “hashtags that hold ideological, theological or political resonance for the group, like ‘Ink of Jihad’, ‘Caravans of the Martyrs’ or ‘Among them is he who fulfilled his vow [to God]’” (Winter 2015, 29). All this to say, that the Islamic State has glamorized the idea of martyrdom (Winter 2015, 29).

Winter (2015) claims that none of these subcategories are discrete nor mutually exclusive but are all present in linear mode apart from the defence subcategory (29). According to Winter (2015), the Islamic State claims to present a comprehensive view of its war to its followers, but in reality it narrates “only the successes of its offensives, while almost entirely excluding its defensive operations” (29).

Utopia narrative: According to Winter (2015), this narrative is most prominent narrative from the rest of their narratives (30); the Islamic State’s millenarian promise, which is the belief by a religious, social, or political group or movement in a coming fundamental transformation of society is the main source of its global appeal (Winter 2015, 30). With this Winter (2015) claims that the group considers itself the sole legitimate in the eyes of God (30). He also points out that the extent which the Islamic State disseminates about its civilian life is unprecedented (Winter 2015, 32).

Winter (2015), furthermore, refines the utopia narrative into 7 subcategories (32):

Religion: With this sub-narrative, the Islamic State projects itself as the only implementer of true Islam (Winter 2015, 32).

“A large proportion of Islamic State’s messaging depicts ‘religious activities’ – people praying and breaking fast together, cigarettes and water-pipes being confiscated and incinerated, shrines being demolished, and so on” (Winter 2015, 33) [see footnote 3 for examples given by Winter].

Economic activity: With this sub-narrative, the Islamic State depicts the “‘flourishing’ economic life under Islamic State” while showing the benefits of migrating to the Caliphate, ‘the land of plenty,’ as the Islamic State portrays (Winter 2015, 33) [see footnote 4 for examples given by Winter].

Social life: This sub-narrative depicts civilian social gatherings such as children playing, and friends fishing together [see footnote 5 for examples given by Winter] (Winter 2015, 34). Winter (2015) claims that, the intention behind this sub-narrative is to give the message that even with difficulties, “life in the ‘caliphate’ is joyful, something that needs to be protected and cherished by any and all means” (34).

Justice: The Islamic State conveying the caliphate as a ‘caliphate of law’ (Winter 2015, 34) regularly depicts its implementation of ḥudūd punishments for civil and religious crimes, and this appeals to a range of audiences such as the ideological supporters, who encourage punishments for religious ‘crimes’, for example, “adultery, insulting God and homosexuality (Winter 2015, 34).

Governance: This sub-category depicts the organization “administering its civilian population, cleaning the streets, fitting electricity pylons, fixing sewage systems, purifying water, collecting blood donations, providing healthcare and education” [see footnote 6 for examples given by Winter] (Winter 2015, 35). Through this depiction, according to Winter (2015), the Islamic State aims to show that it is not only a practicable alternative but also the only feasible option for Sunnis (35).

Expansion: According to Winter (2015), the reason behind depicting expansion “is not just outreach, but also to ensure the perpetuation of that most precious symbolic asset: the perception of momentum” (36).

Nature and Landscapes: According to Winter (2015) this utopia narrative sub-category depicts the beauty of nature providing a further layer of detail to what life is like in the Caliphate thus romanticizing life in the Caliphate. (36).

Winter (2015) claims that the emphasis placed on the civilian aspects of life in the Islamic State is to show that the group itself is not all about brutality as the Western media proposes but more of “judicial order economic plenty, religious piety and social justice (36-37).

Winter (2015) concludes that the Caliphate has a systematically and carefully designed brand (39) that is flexible and constantly changing (38). And contrary to what the Western media portrays, brutality, even though plays an important role in the Islamic State’s imagery, it nevertheless is not “the key to its appeal (Winter 2015, 38). According to Winter (2015), this study shows that “in order to meaningfully challenge the group’s media strategy, all parties in the counter-Islamic State effort must recognize that different things appeal to different people, and thus that success is attainable only through variation” (38). And he, furthermore, asserts that in order to come up with alternative narratives, the parties in the counter-Islamic State need to have a strong understanding of the Islamic State’s narratives in order for the alternative narratives to be effective (Winter 2015, 38).

[1] The first day of Shawwāl is Eid al-Fitr. Some Muslims observe six days of fasting during Shawwāl beginning the day after Eid ul-Fitr since fasting is prohibited on this day. Also see: https://sunnahonline.com/library/hajj-umrah-and-the-islamic-calendar/322-fasting-the-six-days-of-shawwal

[2] “See, for example, ‘Abu Talha al-‘Iraqi, Abu Mu'adh al-'Iraqi (Ink of jihad)’, Salahuddin Province Media Office, 2 August2015; ‘Abu Qa'qaa’ al-Rusi, Abu 'A'isha al-'Iraqi (Caravans of the martyrs)’, Fallujah Province Media Office, 12 August 2015;‘Abu Harith al-'Iraqi (Media man, you are a mujāhid)’, Salahuddin Province Media Office, 15 August 2015; ‘Abu Khattab al- Ansari, Abu 'Abdulrahman al-Ansari, Fadi al-Ansari (Among them is he who has fulfilled his vow)’, Kirkuk Province Media Office, 2 August 2015” (Winter 2015, 29).

[3] “‘Friday prayers in Shadadi’, Baraka Province Media Office, 1 August 2015; ‘The ambiences of 'Id in the city of Fallujah’,Fallujah Province Media Office, 18 July 2015; ‘Confiscation and destruction of a quantity of cigarettes in the city of Harawa’,Cyrenaica Province Media Office, 24 July 2015; ‘Confiscation and destruction of a quantity of water-pipes’, Anbar Province Media Office, 4 August 2015; ‘Removing the tree of Moses (a polytheistic shrine)’, Khayr Province Media Office, 13 August 2015” (Winter 2015, 33).

[4] “‘The flourishing of the markets on the night of 'Id in the city of Raqqa’, Raqqa Province Media Office, 17 July 2015” (Winter 2015, 33).

[5] “‘Felicitations of ordinary Muslims at the advent of 'Id al-Fitr in Khunayfis’, Damascus Province Media Office, 18 July 2015;‘Happiness of 'Id in the lands of monotheism’, Fallujah Province Media Office, 20 July 2015; ‘Muslims at leisure at the Euphrates River in the city of Raqqa’, Raqqa Province Media Office, 21 July 2015; ‘Swimming pools in Mosul city’, Nineveh Province Media Office, 2 August 2015; ‘Outing of the young descendants of Salahuddin’, Nineveh Province Media Office, 11 August 2015” (Winter 2015, 34).

[6] “‘Cleaning and decorating the streets in the city of Sirte’, Tripoli Province Media Office, 19 July 2015; ‘Paving the streets in Sharqat area’, Dijla Province Media Office, 30 July 2015; ‘Repairing the electricity lines in the city of Shadadi’, Baraka Province Media Office, 31 July 2015; ‘Lighting up of Karmeh after the repair of electricity and the return of Muslims to their houses’, Fallujah Province Media Office, 3 August 2015; ‘Fixing the sewage system in Mayadin’, Khayr Province Media Office, 28 July 2015; ‘Fixing the sewage system’, Anbar Province Media Office, 9 August 2015; ‘Water purification plant in the city of Albu Kamal’, Euphrates Province Media Office, 30 July 2015; ‘A water purification plant’, Fallujah Province Media Office, 30 July 2015; ‘Blood bank in the city of Mosul’, Nineveh Province Media Office, 6 August 2015; ‘The Medical ServicesDepartment on a visit to the Medical Centre of the Health Department’, Aden Province Media Office, 28 July 2015; ‘Ba'aj hospital under the protection of the caliphate’, Jazira Province Media Office, 9 August 2015; ‘Second term exams begin in the schools of Nineveh Province’, Nineveh Province Media Office, 15 August 2015; ‘The exams of the qualifying session for teachers in the city of Raqqa’, Raqqa Province Media Office, 9 August 2015” (Winter 2015, 35).