Fall 2017 / Spring 2018

Findings I

Intentionality

Ostovar (2017) suggests that jihadi visuals stress on simplicity and have explanations of intentionality (84) communicating different messages (83).

Based upon this research analysis of the Islamic State’s photographs conducts methodological triangulation. The first step applies the Panofsky method of analysis, which is a qualitative analysis through the understanding and interpretation of meaning in visual representation. According to Panofsky (1972), the study of art objects and photographs can be separated into three levels. The first level is pre-iconographic analysis, which is the formal, natural and factual descriptions of what is seen such as the colours, the content, and the format seen without any speculations (7). Consequently, as a first research step, I applied the pre-iconographic analysis by implementing a quantitative analysis of the photographs. To discuss in details, I created a database of keywords, which includes all 111 photographs with the keywords in terms of factual description including each photograph's composition. To add, each photograph is tagged with its keywords in order to facilitate the search for keywords and to identify the frequency of the elements in focus and the photographic composition and photographic techniques. It is important to note that all elements in each photograph are tagged including mundane ones such as “Adidas running shoes”. Furthermore, the keywords are alphabetically added in a Microsoft Excel sheet and each photograph is tagged with its respective keywords in Adobe Bridge in order to allow finding the keywords and determining their frequency.

Subsequently, the second level of the Panofsky method is iconography, which is the decoding of the content by questioning what the elements in each picture mean taking in consideration the context, history, audiences, framework of society. Having said that, The online report, The Islamic Imagery Project: Visual Motifs in Jihadi Internet Propaganda, serves as a reference point for the iconography method, the decoding of the content by questioning the meaning of the elements in each photo taking in consideration the context, history, audiences, framework of the Islamic States (IS)’s portrait photographs using the quantitative data collected from Rumiyah. First published in 2006 and maintained by the Combating Terrorism Centre, the department of Social Sciences United States Military Academy at West Point, this report analyzes imagery produced by radical Islamist groups. This report claims that the production and distribution of visual propaganda through jihadi imagery produced and distributed by jihadi Organizations have a distinct genre. To add, In The Visual Culture of Jihad, a chapter written in the book, Jihadi Culture: The Art and Social Practices of Militant Islamists, the author Afshon Ostovar (2017), who is also the co-author in the report mentioned above, The Islamic Imagery Project: Visual Motifs in Jihadi Internet Propaganda, states that basic symbolism and visual techniques can communicate meaning (84). Moreover, the authors of the report, Brachman et al. (2006) identify visual motifs based on ancient Islamic traditions, historical, and cultural references that commonly occur in jihadi propaganda (6-7) grounding their findings on imagery that is a mix of graphics and photographs (6). They claim “that these images speak for themselves, quite literally. In most cases, one does not need to be able to read any of the text within the images to understand the broad meanings conveyed” (Brachman et al. 2006, 7). Furthermore, it is worth to note that in this report the authors state that that there is more work to be done in order to thoroughly document the full range of the jihadi visual propaganda in particular with identifying new motifs, which might reflect “changes in ideology” (Brachman et al. 2006, 7). But more importantly, the Islamic State’s visuals are more sharp and polished than the old jihadi visuals analyzed in The Islamic Imagery Project: Visual Motifs in Jihadi Internet Propaganda, which are kitsch and excessive; we certainly cannot disregard the technological advancement from the time those visuals were created to now.

Findings

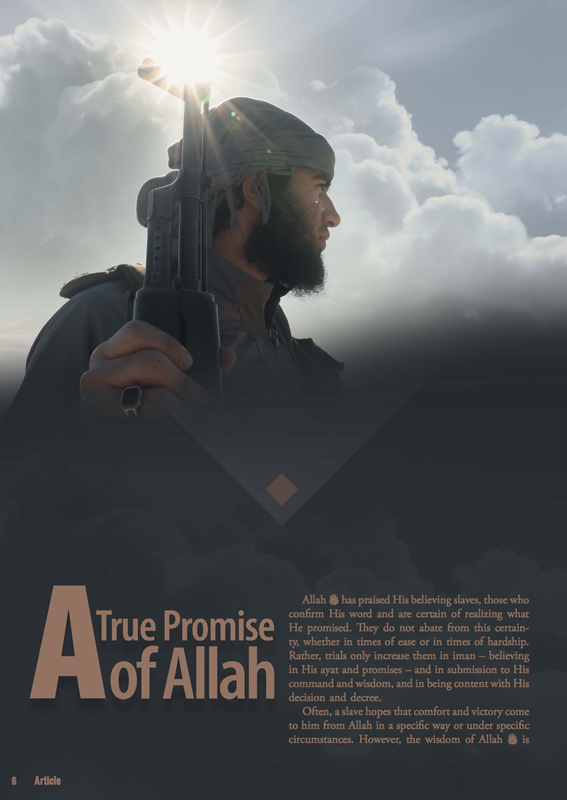

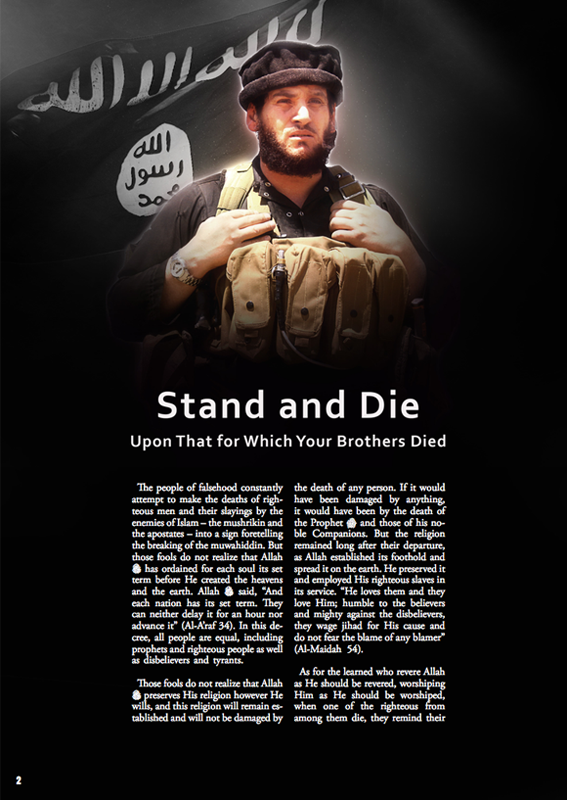

Fighter - MujahidAccording to Ostovar (2017), a fighter/mujahid elicit notions of bravery, strength, and religious devotion; therefore, the designer or photographer presents the fighter in a form suggestive of these traits (93).

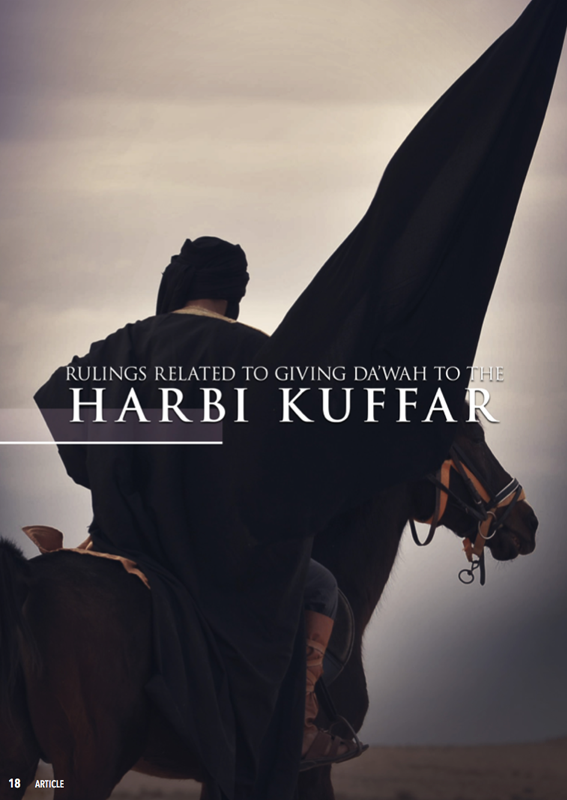

Depicting a fighter in a pre-modern appearance such as on a horse or with a sword suggests notions of Islam’s past (Ostovar 2017, 94) specifically associating with the legacy of Islam’s founding generations (Ostovar 2017, 95) and their early successful jihadi campaigns, which furthermore grants legitimacy to modern jihad as well as the group itself (see pdf p. 113).

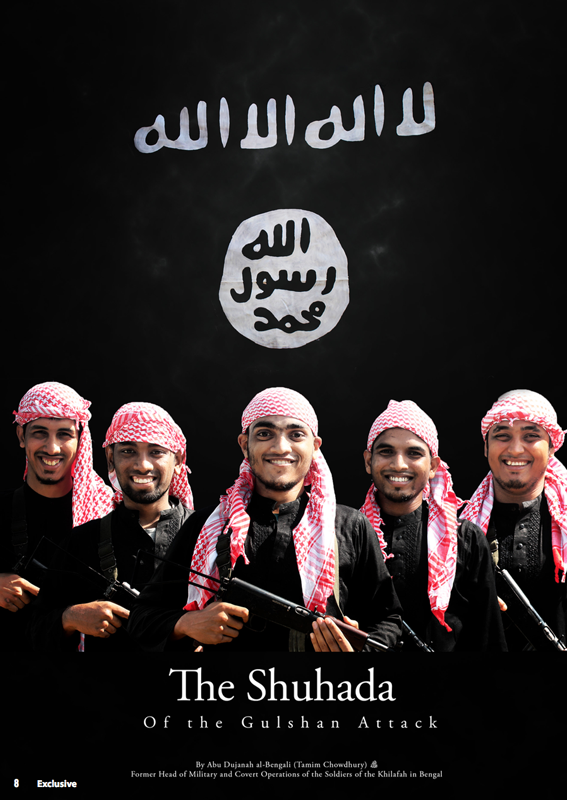

Martyr - Hero…

… and the promise of paradise (the afterlife)

“communicate notions of virtue, heroism, and divine reward” (Ostovar 2017, 93).

“In Islam, there is no greater spiritual act than martyrdom for one’s faith” (Brachman et al. 2006, 86). Therefore, a martyr is singular and is elevated above other believers in the eyes of God (Cook 2017, 152). This preference consists of forgiveness, an assurance of paradise, safety from the suffering of the grave and the terror of resurrection, placement of a crown on the head of the martyr, his marriage to 72 young virgins, and finally intercession for relatives (Cook 2017, p. 153).

The direct access to the vision of paradise signifies that martyrs possess superhuman qualities (Cook 2017, p. 153). (see pdf p. 68 & 103 - Superhero look)

Some Sunni scholars such as Abdallah Azzam, a Palestinian Sunni Islamic scholar and theologian known as Father of Global Jihad and a founding member of Al-Qaida (Bill Moyers Journal PBS), heavily marketed the sanctity of the martyr in contemporary Sunni jihadi mythologies by affirming that in order for Islam to develop as a religion and as a civilization, there must be a will to self-sacrifice on behalf of Islam; this affirmation creates a close connection between suffering/death of the martyr and the success of the Umma (Cook 2017, 155).

Note: For these reasons, martyrdom is advertised and praised; encouraged and celebrated; therefore an important motif in jihadi visuals (Brachman et al 2006, 86).

Martyrs are a source of inspiration and their photographs are used to inspire support for jihad (Brachman et al 2006, 86).

(pdf p. 97 as if martyrs ascending to heaven (pointing upwards and carrying the IS flag) - A call to Paradise - a path of jihad - a path to paradise).

Martyr/Fighter with Quran and weapon

These photographs, generally taken before a suicide mission to mark that event as the “before shot” or “last will and testament” photo, almost always include weapons (modern weapons in the case of the IS in Rumiyah) and the Quran communicating the religious importance of martyrdom and its violent nature (Brachman et al. 2006, 87)

(see pdf p. 44, 56, 73 (possibly Quran), 119).

All Black Dressed

The colour black is regularly used as a colour of protest (Ostovar 2017, p. 100).

The black suggests operating in secrecy and working from the shadows to attack the enemy (Ostovar 2017, 96).

The masked, faceless fighter evokes an intimidating sight, which projects strength, mystery, violence and anonymity (Ostovar 2017, 96).

(see pdf p 103: the jihadist as a shadowy but impressive fighter)

Children

According to Brachman et al. (2006), children are employed in jihadi visuals to call forth notions of pride, honour, as well as, the need to protect Islam from outside harm (90).

Furthermore, photographs of young boys also propose the rise of a new generation of jihadi fighters (Brachman et al. 2006, 90).

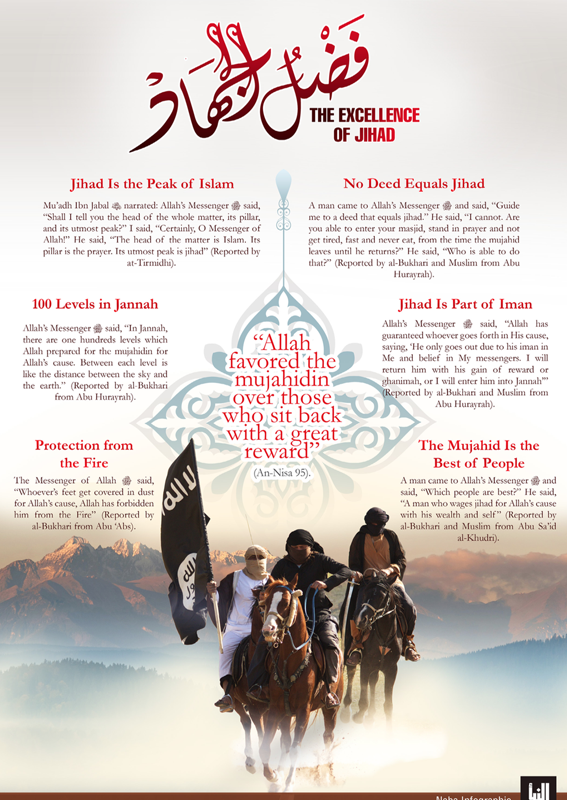

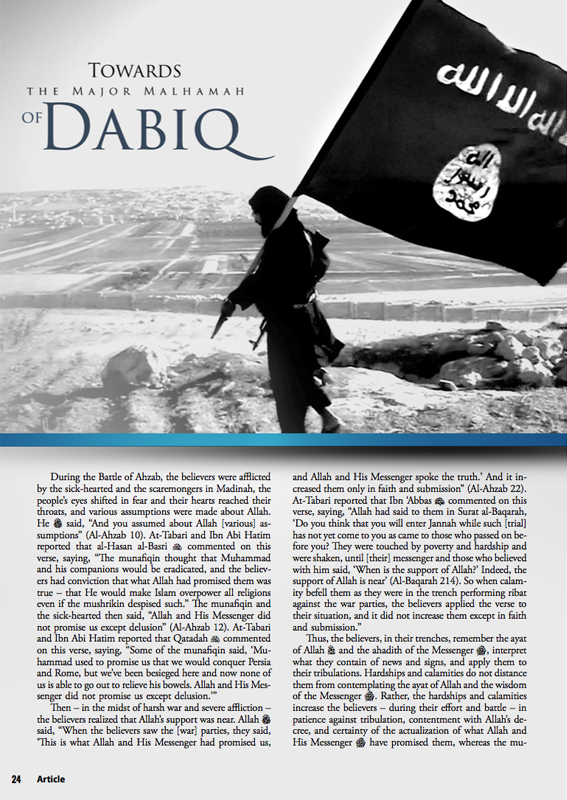

The Islamic State Black Flag

The flag motif is a representation of territory control, a marking of the organization’s territory, advertisement and an announcement of the presence of its forces in a specific location (Ostovar 2017, 87-88).

As seen in the quantitative data, the Islamic State regularly uses its flag in the portrait photographs (28 in totals) for example, in one photograph a fighter holding the IS flag stands on a rock and the background is a vast landscape (see pdf p. 79). Another example is fighters holding the IS flag during a convoy (see pdf p. 5 & 84), which could possibly be a territory victory celebration.

Colour of the flag: Black

The colour black is regularly used as a colour of protest in the Islamic world as well as globally (Ostovar 2017, 90).

To add, even though the colour green is considered to be the colour of the Prophet Mohammad (Brachman et al. 2006, 59), the Islamic State has chosen the colour black rather than green. Ostovar refers to McCants, who states that this choice represents the Islamic State’s Manichean worldview, which accepts only the duality of right and wrong/believers and non-believers (Ostovar 2017, 90).

Furthermore, “Jihadi flags, which are generally black, are meant to represent the battle standards carried by Muslim forces in some of the earliest armed conflict in Islamic history” (Ostovar 2017, 88), even though Ostovar (2017) claims that historical description of the colours of banners used by the earliest Muslims differ from white, green, yellow or black, and sometimes included the Muslim proclamation of faith (88). Moreover, he suggests that jihadist groups interpret history for themselves. Therefore, the flag a jihadi organization adopts manifests this interpretation revealing the group’s sensibilities towards historical purity (Ostovar 2017, 88).

However, in the Islamic traditional and historical context, the black flag evokes the black battle standards used in the eighteenth century Abbasid Revolution that overthrew the corrupt rule of the Umayyad replacing it with a new caliphate based in Iraq (Ostovar 2017, 90). It is noteworthy to mention that the Abbasid not only lead to the Golden Age of Islam but their revolt also played a prophetic expectation of the coming of the Mahdi, the Muslim saviour, who is expected to arrive before the apocalypse to restore justice for Muslims (Ostovar 2017, 91). Ostovar (2017) refers to McCants, a former U.S State Department senior advisor for countering violent extremism from 2009 to 2011 (The Brookings Institution), who argues that the Islamic State deliberately chose the colour black for its flag to connotes this apocalyptic expectation of the prophecy (100).

Moreover, the Islamic State flag depicts the first phrase of the Shahada (at the top) “La Illah Ilallah”, means “No God but Allah”. And the white circle represents the second phrase of the Shahada, “Mohammad rasulullah” which means “Mohammed, the Messenger of Allah”, in the form that according to a statement by the Islamic State in jihadi discussion forums about the design of the flag is the historically accurate seal of Mohammed as contained in the Ottoman records, and the order of the words (from top to bottom: god, messenger, Mohammed) developed by following Islamic oral traditions describing the seal of Mohammad (Ostovar 2017, 89-90). In addition, Ostovar (2017) refers also to Will McCants, who claims that the white circle is deliberately ragged suggesting an era before Photoshop regardless of the fact that the flag was designed by using a computer (Ostovar 2017, 90).

Note: IS Flag - Symbol of Protest

The Flag of the Islamic State has appeared as a symbol of Islamist resistance and political demonstrations across the Middle East and North Africa during the Arab Spring (Ostovar 2017, 91).

Category II: Nature

Sun

According to Brachman et al. (2006), in jihadi imagery, the sun is generally used to evoke association with the divine, and it may be used figuratively (i.e. not photographic) or literally (i.e. photographic) (10).

Figurative

Graphic representation such as golden rays that evoke the rays of the sun, and is usually used to “illuminate” certain symbols, text, or individuals in order to associate them with the divine (i.e. God) legitimizing them spiritually as well as religiously (Brachman et al. 2006, 10).

Literal

The literal depiction of the sun is generally that of the sunrise or the sunset, and is also used to evoke association with the divine (i.e. God) as well as the afterlife (Brachman et al. 2006, 11).

According to the quantitative analysis of IS self-representing photographs in Rumiyah, there seems to be an absence of figurative sun motif (i.e. not photographic). Nevertheless, the literal depiction of the sun is present (for examples, see pdf p. 50, 75 & 109).

Furthermore, in some photographs the IS designer has created a photo-montage by adding light effect (from possible explosions or fire), and has placed a fighter standing right in front of it giving the impression of light (see pdf p. 88). Another example is of a photograph from a video called, “One of the Two Good Outcomes” (see pdf p. 100) in which the designer has added an effect of light as the background of the title of the video in Arabic, and placed it in front of the fighters. Another interesting observation is the uniqueness of a photograph that looks like a movie poster, which I will discuss further later, and also the smoke-like air coming out of the fuel vent tanks of the airplanes. What is interesting is that the designer has placed the fighter in this photo-montage under the strips of air, which give the impression of sun rays.

Moon

According to Brachman et al. (2006), the moon is a highly important and complex symbol in the Islamic culture; it has astrological significance as well as religious and spiritual meanings (12). Nevertheless, its use in jihadi visual propaganda is usually less complex and almost always suggests “aspects of religious identity and notions of the afterlife and the divine. A full moon is usually employed in order to evoke notions of the afterlife and the power of God" ( Brachman et al. 2006, 12).

(see pdf p. 28)

Body of water

According to Brachman et al. (2006), a body of water , generally used as a background element in the jihadi visual composition is generally employed with the intention of evoking notions of purity, the divine, paradise (i.e. the afterlife), and religious piety (17).

(see pdf p. 25 & 47)

Greenery / Vegetation

Greenery (i.e. trees, forests, and other plants) usually used as a background element is very common in jihadi imagery (Brachman et al. 2006, 24). This element elicits notions of the Islamic concept of heaven being a lavish garden

(see pdf p. 24, 55, 80, 81, 91, 92, 98, 101, 109, 111).

Landscape

Mountains

According to Brachman et al. (2006), mountains are a common motif in jihadi visuals and are generally used to evoke spiritual beliefs and make an allusion to the grandeur of the divine (26). They might also serve as a representation of a specific region of concern, and of completed or ongoing operations (Brachman et al. 2006, 25).

(see pdf p. 24, 80, 57, 61 & 64)

Desert

According the Brachman et al., desert landscapes are common in jihadi visuals, and are divided into two categories: sandy or rocky (27).

Sandy Desert

Sandy desert landscape is not common in the Middle East; nevertheless, it is an important marker of Arab-Islamic identity, traditions and cultures, as well as early history of Islam with reference to the first generation of Muslims succeeding in jihad and the purity of their faith; for this reason sandy desert depictions are common by Salafi Groups (Brachman et al. 2006, 27).

(see pdf p. 20, 21, 22, 34)

Rocky Desert

rugged and spotted with shrubs and other flora —is the most common landscape across inhabited regions of North Africa and the Middle East (Brachman et al. 2006, 28). Subsequently, according to Brachman et al. (2006), portrayal of rocky deserts can be reproduces across Islamic cultures of different ethnic and regional backgrounds, which could also in its turn, evoke specific ethnic and regional identities, as well as historical events (28).

(see pdf p. 45, 56, 58, 67 & 114)

Horse

Even though Islamic State’s photographs are contemporary, nevertheless they refer to ancient traditions, historical and cultural references as an attempt to portrait literal and extreme interpretation of the Salafi movement within Sunni Islam. Therefore, the motifs used are easily recognizable symbols within the radicalized Salafi ideology (Brachman et al. 2006, 7). Moreover, as an example of this technique of reference, Brachman et al. (2006) mention the repeated use of photograph of Osama bin Laden on a horse, which connotes the assumption of his kinship with the companions of the Prophet Mohammad (7). According to Brachman et al. (2006) a horse is a very important symbol in Arabic and Islamic culture identifying it “with chivalry, battle, bravery and victory” (33). They also claim that in Islam, a horse suggests as a reference to the first generation of Muslims and their victorious campaigns of jihad (Brachman et al. 2006, 33). Moreover, the authors confirm that the horse motif is used both literally and figuratively to evoke jihad (Brachman et al. 2006, 33).

In the literal use of a horse as a motif symbolizing jihad is rooted in a famous Islamic hadith, record of traditions or sayings of the Prophet Mohammad used as a major source of reference for religious law and moral guidance (Brachman et al. 2006, 33). This hadith states: “He who out of faith in Allah and a firm belief in His promise prepares a horse while waiting for jihad, then its feeding and drinking and its dung are all in his favour on the day of Resurrection” (Brachman et al. 2006, 33).

Going back to the figurative use, the Salafi ideology, the horse suggests purity, which is fundamental in Salafism, which believes that the first generation of Muslims and the Prophet’s companions practiced “true” Islam (Brachman et al. 2006, 33). The reference to traditions, history and culture of the first victorious campaigns of jihad and the notions of the purity of the first generation of Muslims, a horse evokes the purity of jihad (Brachman et al. 2006, 33).

Along with the horse motif, there is also the black flag motif. The combination of a horse, a flag, and a rider, who is also a fighter, are also common symbols in jihadi visuals; in this sense, the combination of these three symbols magnifies the intensity of the photograph (Brachman et al. 2006, 36). Another popular symbol that could be added to this combination is a rider/fighter holding a sword. According to Brachman et al. (2006) adding a sword to this combination “is the most aggressive and explicitly militaristic use of the horse motif” evoking the violent nature of jihad (38). The sword similar to the horse materializes Salafi notions of jihad in early Islam, and is therefore also suggestive of Salafi ideology (Brachman et al. 2006, 38).

“Horses and horsemen are also an important symbol of virility and warfare" (Cook 2017, 159)

Having said the above, in Rumiyah, the Islamic State has also embraces these symbols and has depicted fighters carrying a flag (the Islamic State flag) while riding horses in three of its photographs (see pdf p. 24, 113 & 114), in two of which the horses are galloping (see pdf p. 24 & 114), and in one photograph, the fighters are holding swords and riding galloping horses (see pdf p. 114). It was brought to my attention that Brachman et al. do not introduce the symbolism of a “galloping horse” and its connotation.

Category III: Weapons, Blood & Afterlife

Weapons are highly common motifs used in jihadi visuals (Brachman et al. 2006, 96) “to communicate their dedication to armed resistance” (Ostovar 2017, 84). Furthermore, depiction of weapons can be divided into two categories: pre-modern or modern (Brachman et al. 2006, 96).

Sword - pre-modern weapon -linking the past to the present

Pre-modern weapons as a motif include swords or spears, and are used to suggest first the violence of jihadi struggle in general, and second the jihadi struggle of the first generation of Muslims (i.e. early Islamic history) (Brachman et al. 2006, 96).

According to Brachman et al. (2006) swords are perceived as noble weapons symbolizing purity, nobility, and virtue associated with early Islamic heroes and their jihadi campaigns (96).

Depictions of the sword has an intention of linking current jihadi movements and activities to those of the early Muslims’ successful Islamic jihadi campaigns in order to legitimize their current activities (Brachman et al. 2006, 96)

(see pdf p. 24, 114).

Knife (see pdf p. 19, 78)

>Modern weapons - such as rifles, guns, and RPGs (bazookas)

Modern weapons symbolize

+ the violent nature of jihadi warfare.

+ the power of the jihadists’ military technology.

+ modern jihadi victories.

+ to associate jihadi fighters’ and martyrs’ identities with violent jihadi activism.

+ heroism (in portrait photographs of individuals).

(Brachman et al. 2006, 97)

Pre-modern & modern weapon combination

By combining a pre-modern weapon such as a sword and a modern weapon such as a rifle, a gun, or an RPG, with other symbols, both the connotations of pre-modern Islamic history such as the Salafi notions of the Prophet’s companions and their successful and religiously legitimate jihadi campaigns, as well as, modern jihadi movements are evoked also suggesting a religious legitimacy to modern jihadi movements (Brachman et al. 2006, 98) (see pdf p. 34 & 65 - executions).

Crossed weapons

Crossed weapons usually swords, rifles, and RPGs is another motif evoking not only the same

meaning associated with each weapon but is also used more generally to suggest a group’s

participation in the contemporary movement (Brachman et al. 2006, 99).

The Islamic State has never used the crossed weapon motif in self-representing photographs

in Rumiyah but has 1 photo (as seen on pdf p. 22) in which it has displayed a few rifles pointing upwards at the centre of the photo with child soldiers standing in an orderly manner as an extension of the centre.

As an educated guess combining the symbolism of a rifle reported by Brachman et al. , I claim that placing the rifles at the centre of the photograph, which has a symmetrical composition,alludes with a furthermore emphasis not only on the notions of the violent nature of jihad and the heroism of the fighters but also on the centrality and importance of these 2 notions; furthermore alluding that a fighter is an extension of jihad. It is also worthy to note that the subjects of this photograph are child soldiers, which could also suggest a representation of the future of Islam being in safe hands with the coming generation of young jihadis.

Combining rifle & flag

From the analysis of the flag motif as well as the modern weapon motif analysis, I conclude that the flag in combination with a rifle as background elements of portrait photographs of fighters reinforces the fighter’s association and dedication with the organization, jihad and its cause, furthermore emphasizing the heroism of the individual.

Blood

“Blood symbolizes violence, martyrdom, sacrifice, injustice, tyranny, oppression, and victory in battle” (Brachman et al. 2006, 100).

Blood also evokes

+ the literal violence of jihad

+ victory

+ emphasizing strength and power of the fighter -> inflates his reputation as a successful jihadi.

(Brachman et al. 2006, 100)

Blood Splatters (see pdf p. 78)

Bloody Hand (see pdf p. 64)

According to Brachman et al. (2006) bloody or bleeding hands are usually present with an

object or a gesture for example a bloody hand holding a flag or a sword and a bloody hand

pointing but it was not the case with the Islamic State photos in Rumiyah (111).

In one photo-montage (see pdf p. 78) the designer has added blood splatters on top of a portrait of a fighter who is pointing upwards (blood splatters combined with a gesture and other elements). Red transparency is added on a photo of people walking and the IS flag below it with a man raising his fist holding a knife. Moreover, the visual is accompanied with text, “AND FIGHT THE MUSHRIKIN COLLECTIVELY,” furthermore emphasizing on violence.

(Shirk in Arabic means the sin of worshipping anyone besides Allah.)

In another photo (see pdf p. 64), the subject is a fighter’s hand (palm) on the side of the photo, the fighter’s uniform appears slightly, and the background is blurry tree leaves. I hypothesize that the uniform represents the individual as a fighter, a hero, and the hand represents the strength and power of this fighter, whereas, the background of blurry tree symbolizes heaven.

Category IV: Hands

Hand raised in prayer (see pdf p. 28, 58)

The hands raised with the palms toward ones face, is an act of prayer in Islam (Brachman et al. 2006, 110).

Clasped Hands motif

represents unity (Brachman et al. 2006, 112) - check other sources as well.

hands grasped together in a team-like manner (see pdf 8, 18 & 89)

Circle

The circle is a universal symbol with different meanings. In Islam, it represents unity (see pdf p. 89).

“In Islamic art the geometric figure of the circle represents the primordial symbol of

unity and the ultimate source of all diversity in creation” (Henry).

This photograph of fighters’ hands grasped together in a team-like manner is shot from

God’s-Eye View camera angle that evokes circle, which in its turn also represents unity in

Islam additionally reinforcing the unity representation of the clasped hands.

Colour - Black

As mentioned earlier, the colour black is highly significant in the Islamic tradition

linking it to both the battle flag of Muhammad and to the medieval Abbasid Caliphate.

In this sense, it most often represents jihad and the caliphate, evoking a historical

sense (Brachman et al. 2006, 105).

Black is also used to evoke strict religious piety in both the Sunni and Shiite traditions; for example, the Taliban as well as the Islamic Republic of Iran accentuate the wearing of black turbans and black clothing in general for religious scholars and clergy (Brachman et al. 2006, 105).

To add, the colour black is also utilized as emphasis on the importance of jihad and as a protest in the Islamic world (Ostovar 2017, 90) with a perception of the “need to re-establish the Sunni caliphate” (Brachman et al. 2006, 105).

+ Smiling (… sometimes excessively and creepy)

showing content? victory? pride look? happiness through jihad? friendliness? Fatherly-figure along with jihad? youth?

(see pdf p. 11, 13, 15, 17, 21, 54, 62, 66, 67, 70, 78, 83, 84, 86, 95, 100, 101, 106, 107, 124)

Finger pointing upwards

is the Finger of Tawhid (raising right index finger with exception of 1 photograph where the left index finger is raised in Rumiyah, issue 2, page 37, video 2). The Tawhid is the belief in the oneness of God and is a key component in Islam (Zelinsky 2014). Moreoever, the Tawhid is the first half of the shahada, which is an affirmation of faith, one of the five pillars of Islam, and a component of daily prayers: “There is no god but Allah”, and the second half is accepting Muhammad as God’s prophet. According to Rita Katz, the director of SITE Intelligence Group, the gesture has been used by jihadis for many years including Osama bin Laden (Crowcroft 2015) as well as militants of Hamas during the first Intifada of 1987 according to Romain Caillet, a researcher in the Institute français du Proche-Orient (Ifpo) (BELGA 2014). Rita Katz also states that the Tawhid finger takes on political meaning rejecting governments not following Shariah law (Crowcroft 2015), which is the religious law forming Islamic traditions. Furthermore, in the context of the Islamic State, this gesture is used as a salute by the Prince of the Caliphate, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (Crowcroft 2015; see Rumiyah, issue 13, page 18), as well as, the Islamic State fighters. To add, according to Caillet, in the jihadi context the Tawhid gesture could signify that the individuals using this gesture are ready to die for the Islamic State’s cause in that moment” (BELGA 2014). To add, In the Islamic State’s propaganda, the alternative political meaning that this religious gesture has gained could be familiarized with the Nazi salute or the Power Fist (Crowcroft 2015).

Weapon pointing upwards

(sometimes on purpose and sometimes not i.e. resting / look at camera angle if there is a contradiction)

Considering Romain Caillet’s analysis that the Tawhid gesture used in the jihadi context “could signify that the individuals using this gesture are ready to die for the Islamic State’s cause in that moment” (BELGA 2014), the weapon pointing upwards could not only be a gesture of reinforcement to this concept but it could also signify the individual’s readiness to die for the cause with a fight in the battlefield.

Other Findings

(in Rumiyah) 1 - Reoccurrence of some photographs

Issue 1 page 1 and page 2 (photoshopped)

Issue 6 page 40 (Examples of the Sahaba’s Eagerness to Attain Shahada) and Issue 12 page 4 (Foreword)

Issue 13 page 20 (last issue) and Issue 1 page 8 (first issue) (different angles and different moments) either they have different photographers or it is a photoshoot.

Stories Issue 4 page 28

Important advice for the Mujahidin: Issue 11 page 6 part 1 / Issue 12 page 24 part 2 / Issue 13 page 22 part 3

Establishing the Islamic State: Issue 7 page 6 pay 1 / Issue 8 page 8 part 2

Path to Victory: Issue 2 page 18 part 1 / Issue 3 page 20 part 2 / Issue 5 page 22 part 3 / Issue 6 page 30 part 4

Operations: Issue 1 page 22 (Operations) / Issue 2 page 32 (Operations) / Issue 3 page 42 (Military and Covert Operations) / Issue 4 page 34 (Military and Covert Operations) / Issue 5 Page 36 (Military and Covert Operations) / Issue 6 page 26 (Military and Covert Operations) / issue 7 page 34 (Military and Covert Operations)

CHANGE OF PHOTO IN ISSUE 8 page 26 (Military and Covert Operation) / issue 9 page 42).

CHANGE OF PHOTO IN ISSUE 1- page 32 (Military and Covert Operation) / Issue 11 page 40) / Issue 12 page 40 (Military and Covert Operation) / Issue 13 page 36 (Military and Covert Operation)

The Religion of Islam photo: Issue 1 page 4 / Issue 2 page 14 / Issue 3 page 16 (photoshopped)

2- Movie Poster like

3- No photographer Credit

4- Quran

-> following the Rule of Thirds, which involves dividing a photograph using 2 horizontal lines and 2 vertical lines, then positioning the important elements in the frame along those lines, or at the points where they meet.

(see pdf p. 45, 57)

-> which could mean evoking emphasis on the importance of faith, religion and devotion in jihad

5- Looking Away (finding: heroic / Communist party leaders’ photos / Che Guevara)

6- The old jihadi visuals are kitsch and excessive in comparison to that of the Islamic State, which are more sharp and polished.

7- Blurred Out Face -> Hiding Identity ? -> If so, then why? Is it a leader? not wanting to be identified?

CHECK! DIFFERENCE:

IS populist but more sharp and polished.Al Qaeda (elitist) kitsch imagery

(Arthur Beifuss)

NO NEED TO ELABORATE AND WHAT THEY SIGNIFY ON THE BELOW POINTS YET

• UNCOMMON BETWEEN IS AND AL-QAEDA• NOT COMMON AS BEFORE (in terms of a combination of the below elements and a member) According to THE ISLAMIC IMAGERY PROJECT

• Crescent (White Crescent, White Crescent in Sky, Green Crescent)

• White Rose (/flowers in general)

• Waterfall, Water drop, Water figurative

• Lion

• White Horse

• Falcon

• Snake

• Camel

• Dove

• Weather and Storms

• Geography Political Symbols and States (example: of maps….) - only 1 or 2 - check

• Green Flag

• Victory poses of IS in comparison to victory poses of Al-Qaeda

Bibliography

BELGA. (2014, August 19; updated on 2014, August 20). Voilà pourquoi les djihadistes posent l'index levé vers le ciel. La Libre. Retreived from http://www.lalibre.be/actu/ international/voila-pourquoi-les-djihadistes-posent-l-index-leve-vers-le- ciel-53f371c735702004f7e006a0

Brachman, J., Boudali Kennedy, L., & Ostovar, A. (2006). The Islamic Imagery: Visual Motifs in Jihadi Internet Propaganda. West Point, New York: Combating Terrorism Center, Department of Social Sciences, United States Military Academy. Retrieved from https://ctc.usma.edu/ the-islamic-imagery-project/

Cook, D. (2017). Contemporary Martyrdom: Ideology and Material Culture. In T. Hegghammer (Ed.), Jihadi Culture: The Art and Social Practices of Militant Islamists, 82-107. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

Crowcroft, O. (2015, June 16). Isis: What is the story behind the Islamic State one-fingered salute? International Business Times. Retrieved from https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/isis-what- story-behind-islamic-state-one-fingered-salute-1506249

Ghosh, T., Basnett, P. (2017). Analysis of Rumiyah Magazine. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (IOSR-JHSS) 22 (7). Retrieved from http://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol.%2022%20Issue7/Version-12/C2207121622.pdf

Henry, R. Geometry - The Language of Symmetry in Islamic Art. Retrieved from http:// artofislamicpattern.com/resources/educational-posters/

Geometry – The Language of Symmetry in Islamic Art

Ostovar, A. (2017). The Visual Culture of Jihad. In T. Hegghammer (Ed.), Jihadi Culture: The Art and Social Practices of Militant Islamists, 82-107. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Panofsky, E. (1972). Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance. Boulder, Colorado, USA: Westview Press. Retrieved from https://www.educacion- holistica.org/notepad/documentos/Arte/Panofsky%20-%20Studies%20in%20Iconology.pdf

The Brookings Institution. William McCants. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/ author/william-mccants/

Zelinsky, N. (2014, September 3). ISIS Sends a Message: What Gestures Say About Today’s Middle East. Foreign Affairs. Retrieved from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/2014-09-03/isis-sends-message

.png)

.png)